Virtualization Basics

Table of Contents

Virtualization allows for the multiplexing of different operating systems on the same hardware. This allows for better utilization of system resources and greater flexibility, enabling common processes such as cloud computing.

Virtual Machine Monitors (VMM)⌗

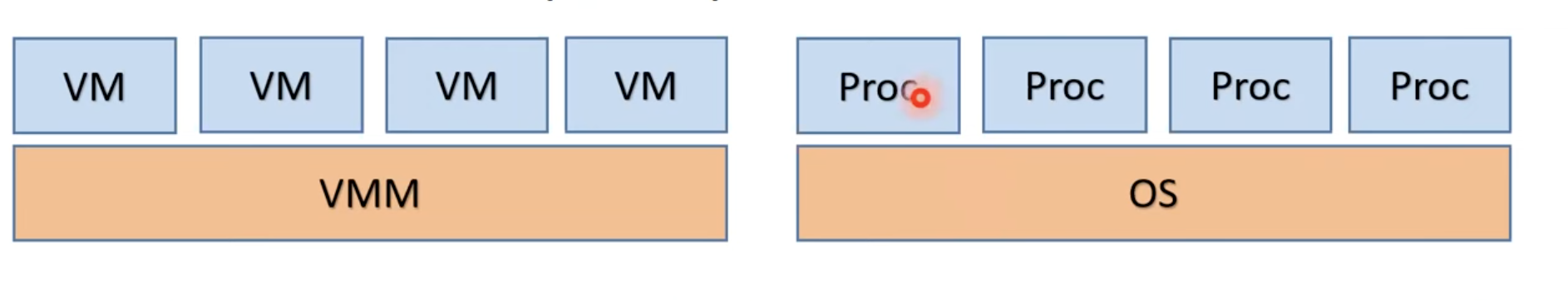

A VMM, or a hypervisor, is at the heart of system virtualization. A VMM allows multiple virtual machines to run on a physical machine, much like an operating system allows multiple processes to run on a CPU.

A VMM performs a “machine switch”, which is the analog of an operating system context switch.

There are some problems in this analogy, however. In a virtual machine, the guest OS expects unrestricted access to hardware (like running privileged instructions). Additionally, a single guest cannot get access to all resources of the machine. Thus, VMMs are designed with special considerations.

Trap and Emulate⌗

User proccesses run in ring 3, OS runs in ring 0. Privileged instructions only run in ring 0. What if the guest OS runs in ring 1, and traps to the VMM in ring 0?

If the guest:

-

Makes a system call or interrupt: The guest process will trap to the VMM (ring 0), which will redirect to the guest OS trap handler. As far as the guest OS is concerned, they simply made a system call to the OS.

-

Returns from trap: Guest OS returns to the VMM, which redirects back to the user process

Issues with this approach⌗

Some registers in x86 show the privelege level. The Guest OS may not operate properly knowing it is in Ring 1 (ex: eflags). Additionally, certain sensitive instructions (those that modify hardware state) can run in privileged and unprivileged modes and therefore do not trap to the VMM.

According to the Popek-Goldberg Theorem trap-and-emulate model only works if all sensitive instructions are subsets of privileged instructions. x86 does not satisfy this criteria.

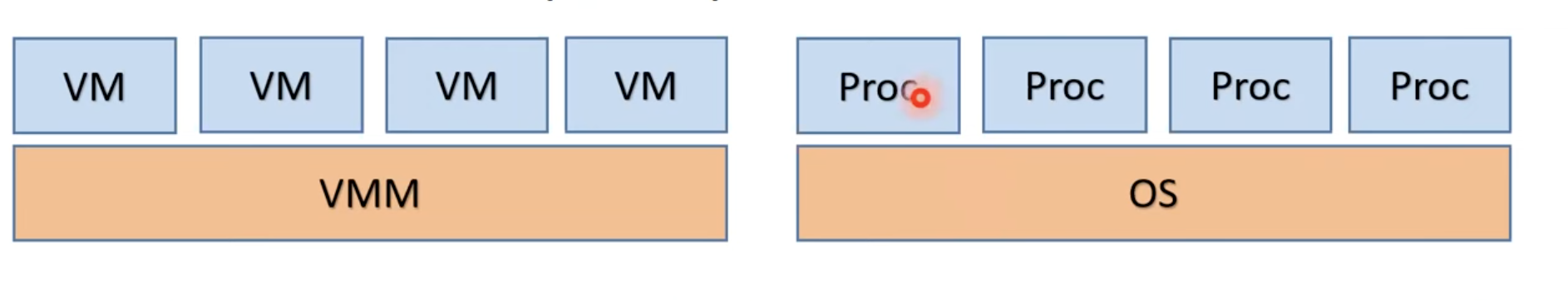

Hardware assisted virtualization⌗

The most common type of virtualization today (used by KVM/QEMU) is hardware assisted virtualization. With this method, the CPU has a special VMX mode of execution.

With VMX, x86 has 4 rings on non-VMX root mode, and 4 rings in VMX mode. The VMM enters VMX mode to run the guest OS in a ring 0 (albeit a less powerful VMX ring 0).

KVM/QEMU Architecture⌗

When the underlying processor supports Intel VT-X or AMD-V, we can use hardware-assisted virtualization.

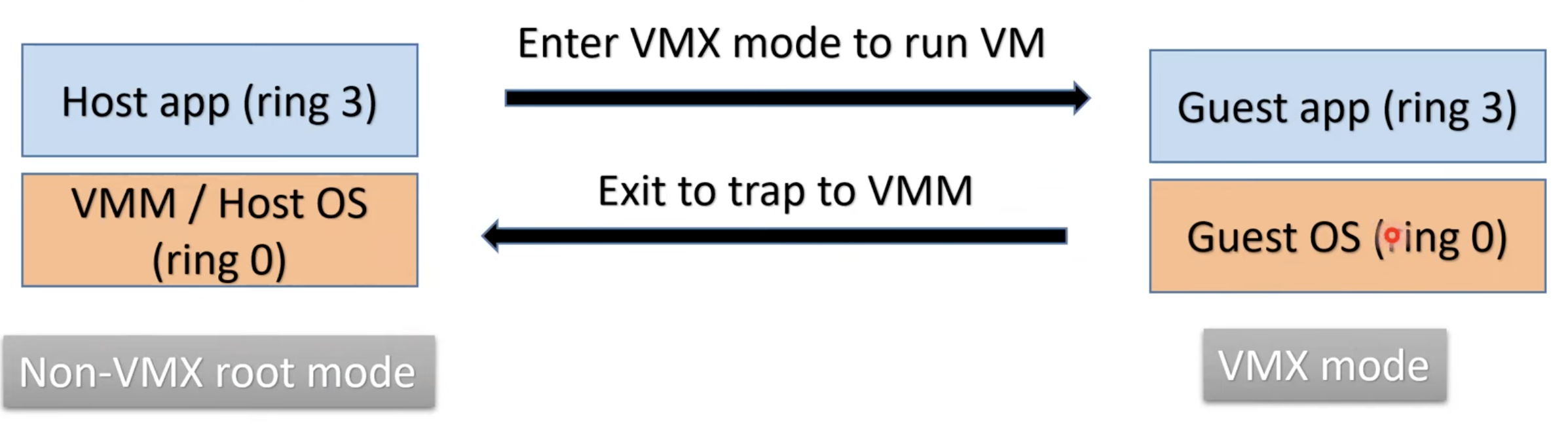

QEMU is a regular userspace process, that communicates with KVM via /dev/kvm device ioctls.

QEMU allocates memory via mmap system call for each guest VM, and creates one thread per vCPU in the guest.

Therefore, the general control loop looks something like this:

open(/dev/kvm)

ioctl(qemu_fd, KVM_CREATE_VM)

ioctl(vm_fd, KVM_CREATE_VCPU)

for(;;) {

ioctl(vcpu_fd, KVM_RUN)

switch(exit_reason) {

case KVM_EXIT_IO: // do I/O in qemu

case KVM_EXIT_HLT:

}

}

VMExits⌗

So when must the guest OS return back to the hypervisor? Whenever this happens, it is known as a VM exit. This is when the CPU transitions from VMX non-root mode to the hypervisor running in VMX root mode.

VM Exits happen whenever the guest performs an operation requiring hypervisor intervention.

- Privileged Instructions

- Memory Access violations (EPT violations): Accessing unmapped physical address, MMIO, ROM

- Interrupts and Exceptions: Hardware interrupts delivered to the host, exception, or software interrupts. VMM must decide whether to inject interrupt into guest, emulate, or handle on host

When a VM Exit is triggered and control is handed back to the hypervisor, the hypervisor either handles the simple exit itself, or forwards the exit to QEMU.

VMX mode⌗

Special CPU instructions enter VMX mode.

- VMLAUNCH, VMRESUME are invoked by KVM to enter VMX mode

- VMEXIT is invoked to exit VMX mode

CPU switches context between host OS and guest OS. During the mode switch, CPU context is stored in the VMCS (VM control structure).

VMCS stores the state of the guest, state of the host, and control fields that dictate how a VM operates. Each vCPU has its own VMCS managed by the hypervisor. This allows the system to easily switch between guest and host state.

Memory Virtualization⌗

Typically, the guest page table has a Guest Virtual Address (GVA) -> Guest Physical Address (GPA) via its page table. Then, the VMM features an additional layer of indirection through the GPA->Host Physical Address (HPA) mapping.

Therefore, the guest’s “RAM” pages are distributed across host memory. With Extended Page Tables support (EPT), we can allow the system to walk two separate page tables for address translation.

I/O virtualization⌗

Each guest OS needs to access I/O devices, but the VMM cannot relinquish control of I/O to a single guest OS. Two ways this is accomplished:

Emulation: Guest I/O operations trap to VMM, which emulates IO in userspace (ex: via QEMU). Direct I/O: Allocates a slice of a device directly to each VM.